photograph (c) Katherine Brown

In the third year of the reign of King Jehoiakim of Judah, King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon came to Jerusalem and besieged it. The Lord gave King Jehoiakim of Judah into his power, as well as some of the vessels of the house of God. These he brought to the land of Shinar, and he placed the vessels in the treasury of his gods. Then the king commanded his palace master Ashpenaz to bring some of the Israelites of the royal family and of the nobility …. The king assigned them a daily portion of the royal rations of food and wine. They were to be educated for three years, so that at the end of that time they could be stationed in the king’s court. Among them were Daniel, Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah, from the tribe of Judah.

Daniel 1:1-3, 5-6, from 1:1-21 [NRSVUE]

Daniel, Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah. Four youths from Judah (the Hebrew calls them ‘children’), ‘of the royal family and of the nobility … without physical defect and handsome, versed in every branch of wisdom, endowed with knowledge and insight, and competent to serve in the king’s palace’ (Dan. 1:3-4). The description of their good looks and amazing insight sounds swoon-worthy until you realize it’s a procurement order. Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, has requested a bevy of these carried-off boys to be corralled, trained, and fed from the king’s own table so that they might in time ‘stand before the king’ (1:4, 5, 18).

To ‘stand’ is the idiom for service, a catch-phrase that can connect this text with last week’s, Elijah’s affirmation that he ‘stands before’ the LORD (1 Kings 17:1). The connection hints at what’s at stake for Daniel and his compatriots. They’ve survived the war. As they endure the captivity, they need to consider. Before whom do they stand? Israel’s God or Babylon’s king?

Babylon’s king is the overt actor. He laid siege to Jerusalem, carried off its treasures, ordered the boys be brought and trained and fed. Yet the chapter is bracketed with references to other kings: the king of Judah, which Babylon conquered (1:1), the king of Persia, which will conquer Babylon (1:21). The frame suggests the transience of earthly powers. Meanwhile, God’s power ‘gives’ Jerusalem into Nebuchadnezzar’s hand (1:2), ‘gives’ Daniel the favor and compassion of the palace master (1:9), ‘gives’ the four youths knowledge and skill in wisdom (1:17). God’s giving is stitched through the chapter, though God is not the actor strutting on the stage.

I wonder what of God’s presence was palpable to Daniel and Hananiah and Mishael and Azariah. Were they aware that God — who had given their homeland to an invader — would give them the favor and knowledge and skill to survive, to thrive in this strange place? What was it that sustained their commitment to stand before the God of Israel even while standing before Babylon’s king? What did they know, or hope? And when?

The chapter pivots at verses 7 and 8. The palace master ‘sets’ Babylonian names on these boys from Judah (1:7), and Daniel ‘sets’ his heart on not ‘defiling himself’ with the royal food and wine (1:8). It reads almost as if he’s shaken himself awake, becomes a speaking actor in the play rather than a prop shunted about the stage. Description gives way to dialogue, the negotiation of the ‘test’: ten days of vegetables (or maybe ‘seeds’) and water, after which Daniel and friends appeared so much haler than the other candidates that they were allowed to continue on their restricted diet. They are allowed to refuse to defile themselves.

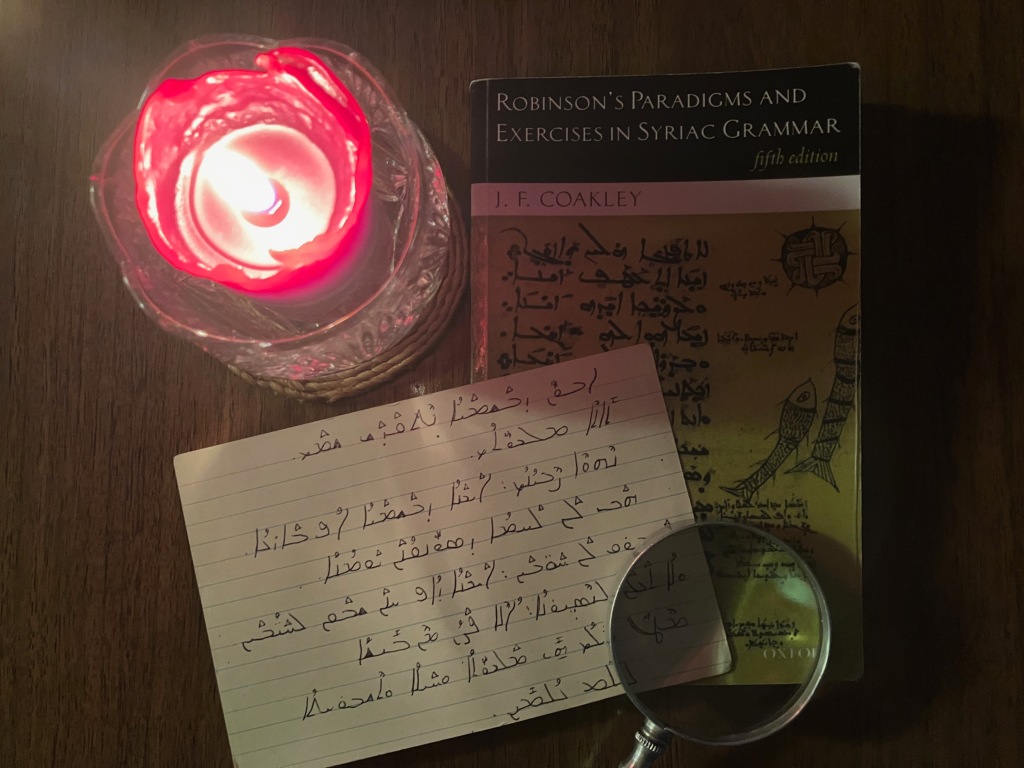

The text never defines how the royal rations would defile. Suppositions are multiple. Perhaps the foreign food violated kashrut. Perhaps the king’s portion is imperial indoctrination. Perhaps the preferred rations echo the ‘seeds’ and ‘growing things’ of Genesis 1:29, as if Daniel and friends, carted off to the king’s gardens in Babylon, will to live as if in God’s garden of Eden.* Or the text is meant to evoke the water and manna of the wilderness: a daily sustaining and a test that leads to knowledge.** Or the text is determinedly indeterminate — staking itself on the explicit claim that this refusal is necessary to avoid defilement, and the demonstration of God’s giving, subtle but sure — while requiring continual wrestling with its possibilities. As Daniel and his friends had to live in the tension of their time, so do we have to live in the tension of the text, allowing it to resist any tidy resolution so that it can speak to our own untidy lives.

How do you know who you are in a setting where everything is not what it was? How do you maintain identity when all around you is strange, even hostile? How do you allow yourself to change without becoming strange to yourself? How do you commit to God’s reign while subject to the powers of the world? This text invites us into the questions not by offering an answer so much as a process. It refuses to conflate God’s kingship and any other but recognizes, even magnifies, the tensions between. (The palace master may change the boys’ names from -of God to -of Babylon; the text itself refuses, uses the names that include God’s name.)

Shake yourself awake. See what’s at stake. Set your heart to stand before the LORD. Hope in God’s giving. Commit to the tension — that’s how the lines sing.

Faith feeds on commitment.

* Anne E. Gardner, ‘The Eating of ‘Seeds’ and Drinking of Water by Daniel and Friends: An Intimation of Holiness.’ ABR 59 (2011) 53-63.

** Michael Seufert, ‘Refusing the king’s portion: A reexamination of Daniel’s dietary reaction in Daniel I.’ JSOT 43(4) (2019) 644-660.